Who discovered Neptune? You might expect the answer to be a name, in the same way that Herschel is always credited with discovering Uranus and Clyde Tombaugh with Pluto. With Neptune, it is not so easy and the full story was the subject of our November Zoom presentation by Carolyn Kennett.

The link between Uranus and Neptune

The story starts with Uranus, discovered as mentioned above, by Herschel and the date is always given as March 13th 1781. This is when Herschel, who was actually looking for comets, saw something which he did not think was either a star or a comet. Further observations convinced him and other astronomers that it was a planet.

The discovery of Uranus led directly to the discovery of Neptune, some 65 years later. Uranus had in fact been observed and its position noted many times before Herschel in 1781 but had always been misinterpreted as a star. There was therefore a small body of information that could be used to infer its orbit and as more was added to this, it became apparent that Uranus sometimes moved faster than normal and sometimes it moved slower. The assumption was that there was some other object beyond it which was perturbing its orbit. Thus the discovery of Neptune, unlike the discovery of Uranus, was not the result of a chance observation. It relied on detailed mathematical predictions based on the orbit of Uranus.

Adams v Le Verrier

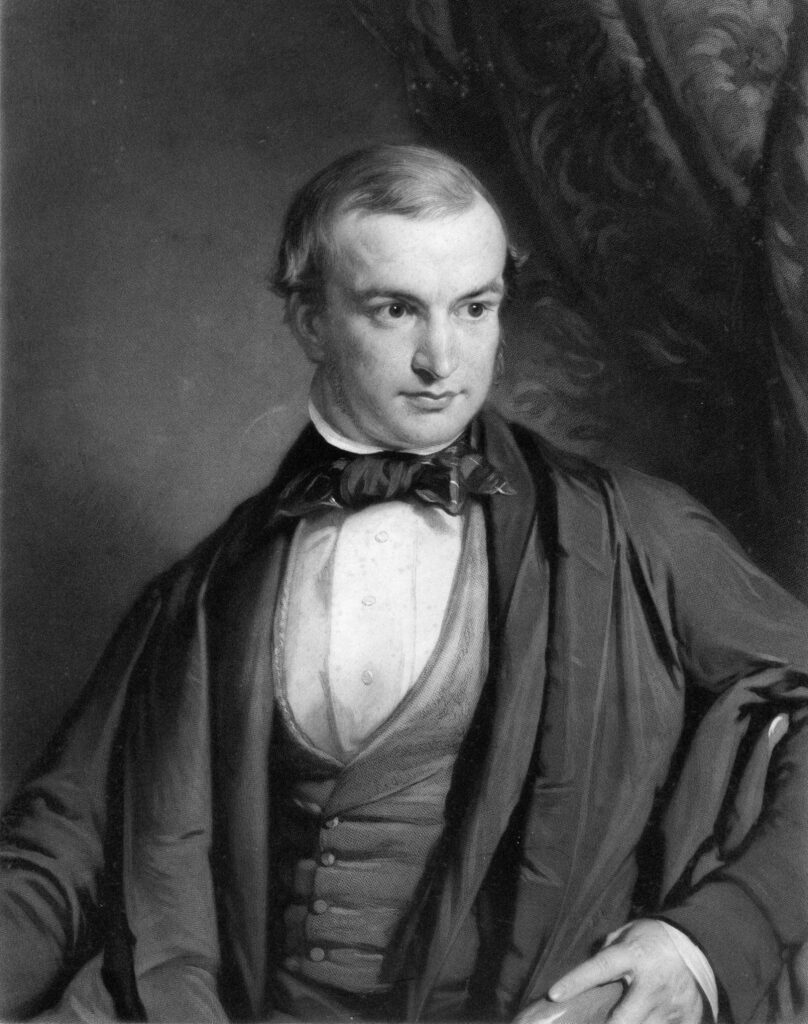

In order to answer our first question “Who discovered Neptune?” , we have to decide between two mathematicians who predicted Neptune’s position from the anomalies in the orbit of Uranus. One was an Englishman called John Couch Adams, the other a Frenchman called Urbain Le Verrier. Our speaker was firmly on the side of Adams, not least because he was born and raised in Cornwall, her home county too.

Adams was an extremely talented young mathematician who had started his education at a small village school and progressed to Cambridge University where he graduated top of his year. He then worked at Cambridge Observatory with James Challis who was able to give him the relevant data on Uranus’s positions from all the earlier observations from which he could deduce the position of the disturbing body beyond it.

Looking for Neptune

When Adams finished his calculations, he was sufficiently confident in them that he contrived to get them handed over to Astronomer Royal Airy in September 1845. Maybe because Adams was of humble background, or maybe because Airy was busy on other projects, but there was no immediate pivot of work to look for a planet at the location Adams had calculated.

Unluckily for Adams (and Airy’s reputation), Le Verrier in France had also completed his calculations and he published them in November 1845 whereas Adams’ work had not been published. This woke Airy up who instructed Challis to start looking at the location predicted by Adams . Challis duly did so and did in fact observe Neptune … without clocking it as the outer planet!

Meanwhile, Le Verrier was keen to find someone to look at his location, eventually giving his data to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. The very first night he had the information, Galle observed Neptune! This was on September 23rd 1846.

Sadly for our presenter, it is Le Verrier and Galle who are usually credited with Neptune’s discovery, with John Couch Adams a bit of a footnote.

So who should get the credit?!

Should it be Galle or Le Verrier who gets the accolade of discoverer? Le Verrier did the hard yards in making the prediction; then it was Galle who first observed it and realised what he was looking at. Without Le Verrier, Galle would never have made the discovery. As I said at the beginning of this post, Clyde Tombaugh is credited with discovering Pluto, yet like Galle he knew where to search because of the predictive work of others.

When listening to the talk, I was struck by the happenstance of the timings of the observations of Uranus. For the anomalies in the orbit of Uranus to occur, it and Neptune must be close to conjunction so that Uranus could catch up then overtake Neptune in its orbit, being accelerated and then decelerated by Neptune’s gravitational field. This only happens every 172 years – and did occur in 1821, exactly the era when there was a lot of interest in Uranus.

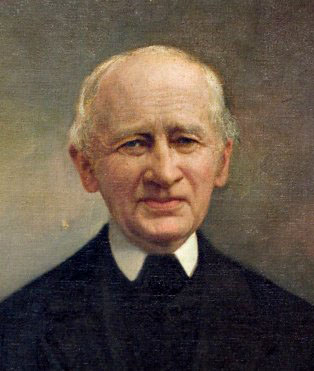

We now have another name to add to the list of those influential in the discovery of Neptune – Alexis Bouvard. He had compiled detailed information about the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, published in 1808 and then wanted to do the same for the newly-discovered Uranus. All he had to go on were the much earlier observations where Uranus had been catalogued mistakenly as a star He found that the current positions were not as predicted by those observations and made further observations which just happened to be around the time of the conjunction. He concluded that there must be another planet outside Uranus creating the anomalies. Thus he set the scene for Le Verrier and Adams work. Maybe he should get some credit too.

Talk given by astronomy writer Carolyn Kennett

Post written by Katherine Rusbridge

Nov 2021